I'm a news junkie. For me, happiness is sitting in a La-Z-Boy watching the pundits talk politics. My favorite show is

Meet the Press. I started watching it when Tim Russert was host. He was the best of the best! I was devastated when he died, but I kept watching the show anyway.

Tim Russert

That habit ended last Sunday. My wife, Susan, was reading a romance and I had just turned on the TV to catch the news. For some reason, the TV was on the wrong channel. Instead of

Meet the Press it was on

This Week with George Stephanopoulos, a show I'd never seen before.

George Stephanopoulos

I was about to change channels, but the show seemed interesting. Five people were sitting around a table talking about the banking crisis. One of them was Paul Krugman, a guy who wanted Obama to nationalize the banks. Next to him was a lady named Cokie Roberts, who was explaining the situation on Capitol Hill. In the middle was George Stephanopoulos, the moderator of the discussion. And next to him was a very interesting man: George Will.

George Will

I was familiar with Mr. Will. In fact, I had read some of his essays, but I'd never seen him in person. There was something about him that caught my attention. His hair was short and nicely combed. His glasses were round; his jacket looked sharp. His demeanor was serious. As he spoke of government and the free market, he seemed intelligent and highly confident. He handled words like an Elizabethan poet. He was witty and coy. His diction was precise; his speech, fluid; his voice, melodious.

He spoke carefully and methodically, connecting one idea with the next, defending each point with flawless logic. His intellect was captivating, even hypnotizing. His knowledge seemed vast and profound. The more I watched, the more entranced I became. The cadence of his voice alone could have charmed a serpent or tamed a lion. He was beguiling, speaking in sentences layered in subtlety and laced with charm. His erudition had a gravitational pull. He was bewitching! When the camera turned to Paul Krugman, I felt abandoned.

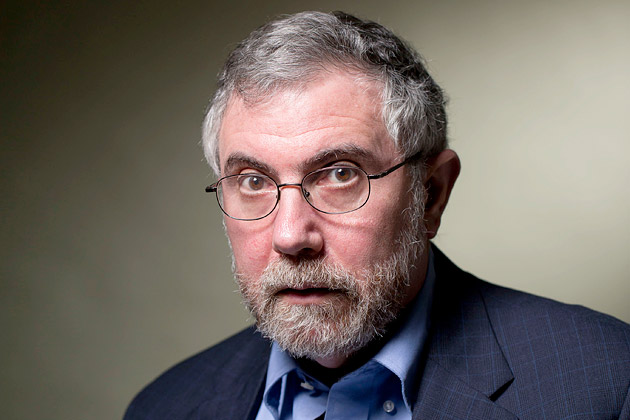

Paul Krugman

I was sad when the show ended. It had conjured a mélange of emotions I had never experienced before -- emotions both complex and incomprehensible. Somehow, a bond had been forged between me and George Will from the shards of language, aesthetics, and deportment. Lost in an impressionistic collage of linguistic virtues, I luxuriated in his rarefied aura.

What was I to do? I was like a schoolboy smitten for the first time. Frightened and exhilarated, I wanted to scream from the highest mountain -- and hide in the deepest catacomb. I was anxious, desperate, and confused -- and all because of

This Week.

That day was a turning point in my life. Distracted, I couldn't concentrate at work. On one occasion, I accidentally wrote Will's name on a patient's prescription. I even called one of my nurses "George" by mistake. At night, I was restless; in the day, dreamy.

Each Sunday, I watched George Will obsessively. I hung on to his every word, delighted in his every gesture, laughed at his every witticism, only to find his departure at the end of the hour unbearable.

Then, one evening, a horrible thing happened: I turned on ABC's

World News. Charles Gibson appeared, and my eyelids began to droop.

Charles Gibson

I then saw myself standing next to George Will in the presidential suite at the Waldorf Astoria.

Transfixed by his presence, I could neither speak nor move. To gaze at his divine countenance was to experience awe and ecstasy. He was a conservative; I was a moderate. But as I peered into the deep azure of his eyes, I felt myself drifting slowly to the right. The top button of his shirt was undone, making the moment even more surreal: George Will, the icon of American conservatism, was tieless!

I felt flush. My knees were weak. I was lost in his hallowed radiance.

Then came a moment of ineffable grandeur: He raised his delicate hand and gently touched my cheek. At that instant, I felt as if I had risen to heaven on the wings of angels.

Closing my eyes, I could feel his breath. Our lips drew closer ... and closer ... and closer ... until finally ...

I awoke, drenched and terrified. My heart was pounding; I was gasping for air.

I ran to the kitchen. There was my beloved wife, Susan, making dinner. She was preparing my favorite meal

-- filet of sole. The radio was playing a romantic song and she was humming along.

I looked at her: Here was the love of my life -- my darling wife and closest friend -- the woman I had vowed to honor and cherish forever. Here was the woman I had laughed and cried with a thousand times, the woman I had kissed and fought with a thousand more.

Nothing was going to ruin my marriage! Not sickness, not poverty, not George Will. I had to find a way out of this inferno, and so I made an appointment with a longtime friend and psychiatrist, John Pfefferbaum. We met in his office the next day.

For an hour I talked about my infatuation with George Will. I effused over Will's swan-like neck and his perfect command of the subjunctive mood.

Afterward, I was embarrassed. I couldn't look Dr. Pfefferbaum in the face. For a moment, I remained silent. Then, unable to endure the silence any longer, I expressed my deepest fear.

"Is it possible that I'm......?"

Dr. Pfefferbaum smiled consolingly. "Let's not jump to conclusions. I need to ask you a few questions. First, have you ever been attracted to men before?"

"No," I replied.

"Are you attracted to the male physique?"

"No," I replied.

"Are you liberal?"

"What?" I exclaimed. "What does that have to do with anything?"

"Well, Steve, there's a condition called Willophilia, which affects liberals. You see, George Will makes no sense to liberals. When on rare occasions he

does make sense, it causes cognitive dissonance. To avoid confusion, the liberal mind converts the dissonance into something more accessible -- eroticism."

"Wow, that's fascinating," I said. "The condition must be rare."

"It's very rare," he said, "although it is slightly more common than Lehrerophilia, which afflicts some PBS viewers."

Jim Lehrer

"How interesting," I said. "You know... now that you mention it... I knew a guy once who was attracted to Brian Williams of

NBC Nightly News, and he..."

"Oh, that's gay," Dr. Pfefferbaum interrupted.

Brian Williams

"Fortunately," he continued, "your condition is both treatable and curable."

I was relieved. "Good. What's the treatment?"

"Just stop watching George Will," he said. "No more

This Week."

"Very good," I replied. "At what rate should I taper?"

"There's no taper," he said. "Just stop cold turkey."

I felt my heart racing.

"Well ... ummm ... wouldn't it be better to cut back to every other week, then every third week, then..."

"Stop it, Steve!" he admonished. "That's the Willophilia talking."

I felt humiliated. Staring at the floor, I struggled to hold back tears.

Dr. Pfefferbaum sensed my agony and spoke assuagingly: "Steve, you can do this. I have confidence in you. Just watch

Meet the Press. You like that show."

Inconsolable, I muttered sheepishly, "But David Gregory sucks."

"I know," replied Dr. Pfefferbaum. "But right now, he's your best option."

David Gregory

I left Dr. Pfefferbaum's office and drove home. On the way, I thought about Susan and all that she meant to me. Dr. Pfefferbaum was right: I

could and

would overcome this!

To purge myself of any erotic impulse, I watched the

CBS Evening News with Bob Schieffer.

Bob Schieffer

My first week without George Will was unbearable: I was moody, anxious, and nauseated. But by the second week, my symptoms began to fade, and by the end of the month, I was back to normal.

The following day, I noticed that my beloved Susan had gone to bed early. The TV was on, and she was watching Casablanca for the twentieth time.

I crawled into bed and hugged her tightly. She looked at me lovingly and said, "Honey, it's been a long time since we cuddled."

"I know," I said, "We should do it more often."

We both smiled and held each other tenderly. Before the movie was over, Susan fell asleep in my arms. I turned off the TV. I then gently caressed her golden hair, kissed her softly and, making sure not to wake her, whispered in her ear, "I love you, Susan. I will always love you."

And from that crepuscular world between sleep and wake -- between consciousness and unconsciousness -- I heard her murmur almost inaudibly:

"I love you, too, Diane."